How to Start Up (Accidentally)

Share On

"I never planned on 'disrupting' the personal fitness industry — all of this happened by accident"

My very good friend (+ previous co-founder) Jonny Nassimi and I have a perpetual, ongoing debate on how to start a startup. There are two schools of thought.

1. Study-up, do your research and make a plan. You’re about to invest a lot of time (your most valuable resource) into something, and you better make sure you’re building something truly worth your time.

2. Build something small and useful — either because you want something that doesn’t exist or literally just want to have fun. It may be a waste of time, yes, but worst case you build yourself something you wanted and had fun doing it.

Every founder faces this debate. Whether we’re on summer break or putting in those few extra hours outside of work, we all must decide how we spend our time. Do we plan or do we build?

I tend to lean on the “just build” side. Not because it’s easier, or more nonchalant, but because I think its the best way to start up — even though it may not be your intentions at the time.

I’ll explain.

Around two years ago, Jonny and I were working hard on ShopTurn, a company that made in-person returns on behalf of consumers in exchange for a small fee. We had just graduated from Techstars, had ample funding and were making very good progress. We had a plan and we were executing. This was around the time HQ was going viral, so naturally, at 3pm every day, nearly everyone at our WeWork would huddle up and try to win HQ.

At one point or another, Jonny and I realized we could build a tool that would google HQ’s questions, and make an educated guess on what the answer might be. It didn’t always work, but it worked well enough. We put it online so friends can use it, and gave it a funny name — HQuack. Word got out, and before we knew it, HQuack had gone completely viral, hitting over 250k sessions within 30 days.

After a lot of debate, we came to the conclusion that removing the site would be the right thing to do. It was ruining HQ for others, and we had no intentions to ruin a game we love so much. But you know this already.

What you may not know is what we did next. We felt like it would be a shame to take down such a popular site without establishing relationships with our users first. To fix that, we replaced the site with a sign up form to be notified of future products we may release. It worked, and within a week we collected 150k emails.

At this point in the story, we were faced with a unique opportunity:

What to do with a mailing list of 150,000 people who play a live mobile game show….

Create our own game of course! After all, every Uber has its Lyft, and every Instagram has its Vine. 😉

We always thought HQ was a bit alienating to people who didn’t like trivia, so we put our own little spin on the game format and published MajorityRules. Our game was different in that users had to guess the most popular answer to a free response question, instead of the correct answer to a multiple choice question. Sort of like Family Feud. 🙌

At its height, MajorityRules hit the 15th spot in the App Store under Trivia > Top Charts.

We had fun, squashed many bugs and worked very hard. We didn’t stay on the top charts, but we most definitely built a product that was entertaining, engaging and functional.

Eventually, we piqued the interest of a company called PeerStream(PEER). They made an offer, we accepted, and only a few months after starting MajorityRules, we sold it.

And boy, did it feel good.

Jumping into the startup world comes with big risks. Deciding to pursue ShopTurn meant Jonny and I turning down some enticing post-grad job offers. To have our work even slightly validated in such a risky industry felt really good. It instilled a newfound confidence in us to continue building and follow our dreams.

And to think—it all happened by accident. There is no way we could have foreseen that starting an HQ answer bot would lead to this. Steve Jobs’ quote from his 2005 Stanford commencement speech finally started to make sense:

You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future.

After the acquisition, I was yet again faced with a very important question. What do I do with my time? Do I research industries ripe for disruption? Or do I work on my smart door buzzer?

I began looking through my old passion projects, looking to see what had potential. Maybe, I thought, there was a dot waiting to be connected.

There was one project which seemed perfect—LiftLog.

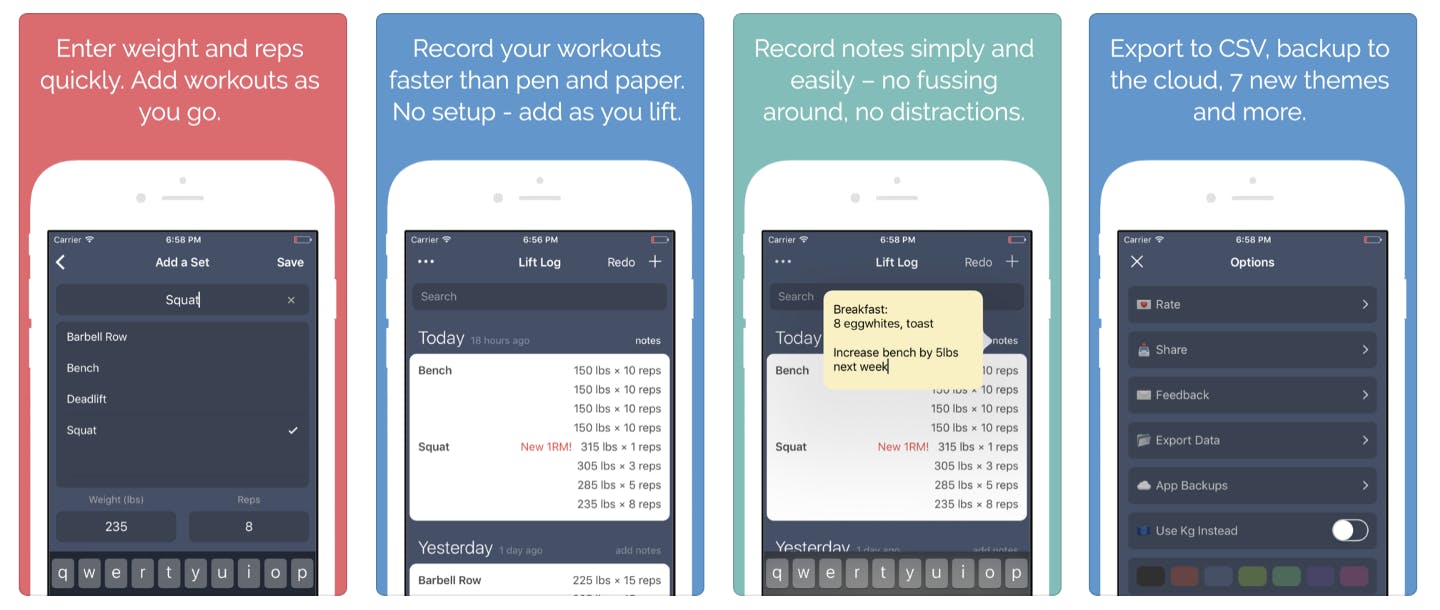

LiftLog is an app I made in college that allowed me to easily and efficiently keep track of my weightlifting. I made LiftLog because similar apps felt like overkill, requiring way too much of my attention mid workout. Plus, building it was much more fun than studying for finals. So during my Sophomore year, I pushed it to the App Store and forgot about it.

I monitored it every now and then, and pushed a few updates. I knew users loved it, because it received stellar reviews and retention was off the charts.

Although it never went viral, LiftLog was consistently downloaded around 30 times a day, and out of around 40k users, many of them used it religiously over the course of three years.

At first I decided to monetize LiftLog itself, so I changed the price from free to $2.99. No luck. Downloads went down to only ~4 a day. Free ramen, yes, but definitely no Tesla anytime soon.

Then, I remembered something: all the workout data my users were generating was being stored in the cloud. I was surprised by how much data I had collected (almost six million workouts) and that I couldn’t find a publicly available weightlifting dataset bigger than my own. I began analyzing everything, and found a clear disconnect between those who made progress over the years, and those who didn’t. The reason seemed obvious—people weren’t increasing the difficulty of their workouts. In fact, most people lifted the same amount, every time they performed an exercise

What surprised me is that less than 8% of my active users actually saw any real progress. I wondered if people were simply more interested in maintaining their strength as opposed to building strength, but that wasn’t the case. After a quick survey I found that 71% of my active users were actually looking to get stronger.

Now that’s a disconnect worth monetizing.

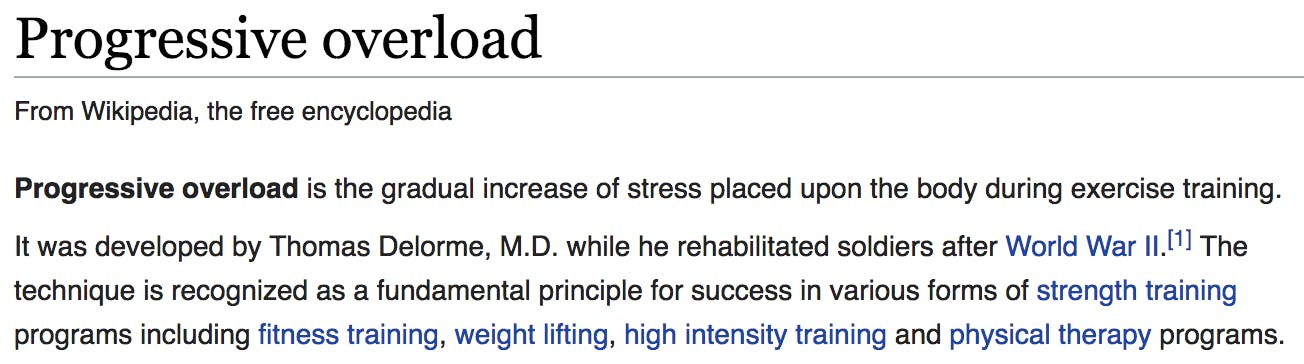

I did a bit of googling and eventually learned about progressive overload.

I knew it was legitimate because it completely coincided with all the data I collected. What I needed to figure out was whether or not there is an optimal schedule to follow in order to build the most strength over a period of time.

I tasked myself to answer the following questions using LiftLog data:

1. How often should an exercise be performed?

2. What is the optimal amount of difficulty to increase an exercise by between workouts? Do we ever decrease the difficulty?

3. Do we alter the difficulty by increasing the number of reps, or the amount of weight (or both)?

Much brainstorming, coding and designing later, I landed on FitnessAI. A highly effective strength training algorithm, wrapped in a beautifully simple and elegant iPhone app – the perfect weightlifting trainer, right in your pocket.

FitnessAI users see a 20% increase in total volume lifted in their first 30 days on average. If you or a friend is interested in weightlifting, check it out for yourself.

FitnessAI stands on the shoulders of 40k weightlifters who used LiftLog more than 5.9 million times over a 3 year period.

And remember, I never planned on “disrupting” the personal fitness industry — all of this happened by accident.

In conclusion

Since you can only connect the dots looking backwards, there’s really only one thing you can do to increase your chances of success – make a shitload of dots.

Here’s how:

1. Build something for YOU

Take a few weeks and build something you can start using immediately. If you want something, it’s likely other people want it too. Don’t waste time adding complicated features, just get the job done quickly. After all, this is mainly for your own use.

If you aren’t a coder, that’s no excuse. My friend Joshua Brueckner created and scaled his company AirTailor, an on-demand clothing alterations service, exclusively using AirTable and Zapier!

2. Make it Available

You don’t know if the dot you’re working on now, may connect to a dot in the future, so store everything from email addresses to usage patterns in the cloud for future reference. It’s sometimes easy to omit things like analytics and SEO for “small side projects” because it’s tedious work—just take time time and do it, because you never know how this dot may connect.

3. Tell your Friends

After you’ve published your side project, tell your friends about it. Post it on Product Hunt! Definitely don’t spend money marketing it. You’re really just sharing something cool you made, and giving it a chance to take off organically.

4. Repeat

Here’s where most people mess up: Drop your current project, and start a new one. It’s easy to become attached to what you’re building. You’ve worked hard on it, and you want to make improvements. Don’t. The time you spend improving something that may not have potential, could be spent creating something that has more potential. In other words, your return on time invested diminishes, so it’s smarter to start something new.

5. Look Back

Every now and then, glance back at your projects. Analyze the feedback you’ve gotten and the data you’ve collected. If there’s a small following, push an update and make your users happy. If you find out something interesting, write about it on Medium! When you hit gold, you’ll know it, so don’t trick yourself into thinking it.

Just remember that patience is 🔑

Comments (5)

Asley Patricia@asleypatricia

perfect..

Share

If anyone wants to own a start-up in all kinds of industries, you must need a killing master plan according to your industries. A great number of people want to start up a business or an eCommerce but they are not successful. I am starting my professional academics career with Reliable Assignment Writing Service London provides leading and highly creative writing services based in the UK.

To run our business successfully. First, we need to develop a start-up plan tailored to your business. I am a professional CV maker, and next year I will be starting my agency for career-building services, offering affordable CV-making services in Dubai. Many people want to start a business. Some are successful, while others fail.

As a student, I think that the phrase “starting up a business by accident” is very interesting. It shows the usefulness of exploiting unavoidable circumstances. However, I do find it difficult to balance my studies and entrepreneurial practices. In case I ever feel like I am in the deep waters and cannot handle things myself, I might think of someone whose service is pay someone to do my dissertation so that I can concentrate on my academic pursuits and grow in such an interesting field!

More stories

Sanjana Friedman · Opinions · 9 min read

The Case for Supabase

Vaibhav Gupta · Opinions · 10 min read

3.5 Years, 12 Hard Pivots, Still Not Dead

Kyle Corbitt · How To · 5 min read

A Founder’s Guide to AI Fine-Tuning

Chris Bakke · How To · 6 min read

A Better Way to Get Your First 10 B2B Customers